In this article, Jamie Keddie describes a technique which involves creating personalized corpora for use in class.

In this last article in the series, I would like to describe a technique that I have been using with my learners which involves creating personalized corpora. Although this may sound like a daunting task, it actually involves nothing more than building up a large Microsoft Word document of all the language that is met in class.

'Like tears in the rain'

These words, spoken by Rutger Hauer in Ridley Scott's Bladerunner, were used to describe how memories are lost when a consciousness dies. I would like to suggest that the image could also be applied to words that are met in the language classroom in cases when there is no intention to recap or revise them at later dates.

In this article, we are going to look at one way in which the words that our students produce may be kept and used as a basis for language study further on down the learning road. Having each of your learners build up a personal corpus is a continual process that can take place over the duration of a term, an academic year, or perhaps just an intensive fortnight. Although it will take a little bit of organization and commitment from both student and teacher alike, once a routine is established, the result will be an invaluable tool for language revision and self-study.

Texts

A personalized corpus can be built up of both imported texts (those that are brought into the classroom for study) or emergent texts (those that the students create themselves). It could include any of the following:

Imported texts

- Transcribed listenings

- Articles

- Quotations (see the second article in this series)

- Song lyrics

- Texts taken from the coursebook

- Transcribed film dialogues

- Emails and letters

Emergent texts

- Any student composition (stories, letters, emails, postcards, etc)

- Any email or mobile phone message that a student sends you

- Any good, well-formed piece of language that you are proud of a student for producing

- Anything that a student says that you correct (and then take a note of)

From handwritten to digital

A personalized corpus will require that texts are obtained in digital format (i.e. typed on a computer, for example). Here is one procedure for converting texts that are handwritten to digital format:

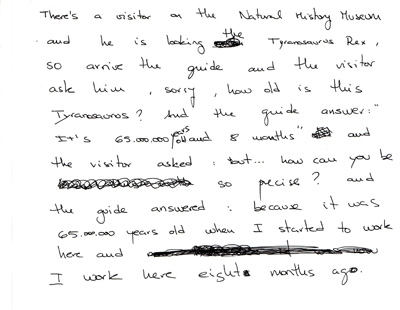

Step 1: Student produces a handwritten text.

|

Step 2: Teacher offers corrections or suggestions for improvement.

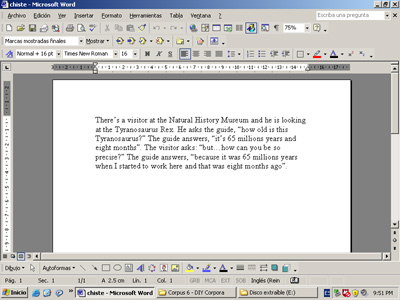

Step 3: At home, student types up the new, improved version on a Microsoft Word document. He or she sends a copy to the teacher as an email attachment.

|

From spoken to digital

At the end of the class, make sure that each learner has taken a note of any utterances that were praised or corrected (see the second and third bullet points under Emergent texts above). These should then be sent to you in the way that has just been described.

Here are a few genuine examples of student utterances that have been added to personalized corpora:

'Coral is craving cheese and lettuce because she is pregnant.' (Marta)

'There are no rats in my kitchen.' (Miquel)

'Jamie can't afford to buy new clothes.' (Miquel)

'My flight was delayed and I could have missed my connection.' (Marta)

'I like men who wear glasses because they look intelligent.' (Coral)

'I'm cold. I'm going to get my jumper from downstairs.' (Coral)

External texts

Most of the texts that we use for intensive reading activities (coursebook texts, newspaper articles, etc) are usually quite small. This means that it is not too big a task for a student to get into the habit of copying them onto Word documents at home. In fact, this provides a genuine reason for an additional meeting of the language that the texts presents and that is always good.

If you are using material from the internet, the copy and paste functions on your computer can be used to transfer the text to a Word document which can then be sent to learners. N.B. After pasting web text into a Word document in this way, it is a good idea to highlight the text and convert it from 'web' text to 'normal' text by selecting 'normal' from this dropdown toolbar.

Creating the corpus

Each learner should create his or her own corpus of all the texts that have been mentioned above. The corpus is nothing more than a Word document that gets bigger and bigger as more texts are added to it (by cutting and pasting).

It is important that the teacher does the same. In order to do this, you have to insist that all texts are emailed to you. This can become a standard routine homework for your students.

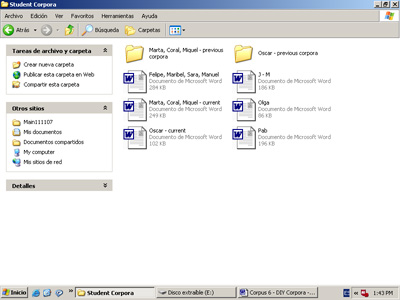

It makes sense to name corpora after your own students:

|

Whether or not your students want to add each others' work to their own corpus is a decision that has to be discussed with them. For J-M, Olga, Pab and Oscar (see screenshot above) this is not an issue since these are my one-to-ones. As a general rule, the smaller the class, the easier it is to manage and keep on top of the corpus.

Once a personalized corpus has grown a bit, it is ready for use in and out of class.

Use in the classroom

Personalized corpora provide both teacher and learner with an instant reference to previously-met language. Imagine the phrasal verb to turn out comes up in class and you are sure that your students have met it before. Open the class corpus Word document, click on Edit in the top left-hand corner of the computer screen, select Find and use the window that pops up to locate the item in question.

In this example case, the words to type into the search window would be turned out. If nothing is found, the process could be repeated with any of the following:

turns out

turn out

turning out

A located item will be highlighted in black (see below):

|

Of course, access to a computer in class is necessary for this. Although your own laptop would be the perfect accessory for this purpose, a class computer and a memory stick containing your students' corpora will work just as well.

Creating activities

In the first two parts of this series, we looked at a number of activities and exercises which involved language that was obtained using the corpus principle. Similar activities and exercises can be made for your students using examples of English taken from their own collection of texts that have been built up.

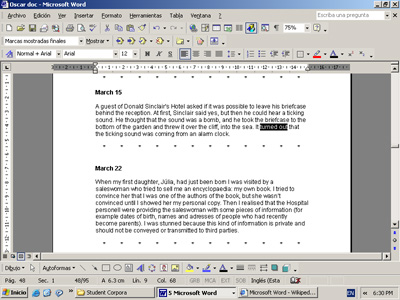

Let's imagine, for example, that you want to find all of the conditional sentences that one of your learners has already met. Open his personalized corpus and, using the same search facility that was described above, you could type the word if into the search window. Every case of this word will be highlighted and this will mark any conditional sentences that are in there. Even if you only find a few, this will be enough for revision or language study.

Here are eight sentences that I found in the personalized corpus of one of my groups:

And I know that if you loved me too, what a wonderful world this would be.

If anyone calls for me, tell them I'm out.

'If the attack hadn't happened, Zapatero wouldn't have won the election.'

'You throw it at the wall and if it sticks, you know that it's ready.'

'Even if you knew that it was the wrong thing to do, you would probably still do it.'

'If I lived in London, I would be scared to drive.'

'If I didn't have children, I would like my life to be like Jamie's.'

Such sentences are taken out of context and the natural first step would be for a learner to recall any of the following:

- What text is the sentence taken from? (For example the first is from Sam Cooke's song, Wonderful World.)

- Who said what and when?

- What were they talking about? (The student who said the fifth sentence, for example, was talking about the temptation to jump into water when being chased by bees).

It would be very useful for your students if you were able to reactivate their experience of the language by showing any images that were associated with it (see the third article in this series). This step could be followed by language study – noticing patterns, grammar, collocations, etc. (see articles four and five in this series for ideas). Finally, after lots of drilling and pronunciation practice, your students could translate the sentences into their own language, and then attempt to translate them back into English.

Here are a few more example language study activities that I have used in the past:

- Problem: Student is confused by the verbs let, lend and leave.

Search: let; lend; lent; leave; left

Activity: Use all examples to create a gap-fill exercise. - Problem: Student mispronounces adjectives which end in –ous.

Search: ous

Activity: Drill the sentences that contain the adjectives. - Problem: Student is unsure about when the verb to get is used

Search: get; got.

Activity: Student looks at all examples and matches the cases of get with synonyms that you have given (receive, find, buy, etc). - Problem: Students want to revise question forms.

Search: ? (i.e. a question mark)

Activity: Student writes answers to questions, questions are then removed and students have to reconstruct them from memory/using knowledge of grammar. - Problem: Student wants to know what words containing the letters ow are pronounced /əʊ/ (slow, crow, below, etc.) and which are pronounced /aʊ/ (down, town, crown, etc)

Search: ow

Activity: Student sorts all examples in two categories (/əʊ/ and /aʊ/). The sentences that contain the ow words are then drilled (i.e. the words are drilled in context).

Use outside the classroom

The more a personalized corpus is built up and used in class, the more a learner will realize its value. This in turn will increase the likelihood that he or she will refer to it outside class. Once a course has come to an end, it can be a good idea to convert all the text to a pdf (Adobe Reader) file. Scans of student artwork as well as relevant photographs or downloaded images can also be included.

Picture by Olga |

Such a portfolio would allow a learner to look over an entire language course at any time in the future.

Conclusion

If a teacher uses language that is taken from a personalized corpus for the purpose of language study, he will be able to kill two birds with one stone:

- First of all, his learners will be looking at the language point in question (grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary, etc).

- Secondly, his learners will be revising language that they have already met.

Everyone has their own way of doing things when it comes to computers. The method that has been outlined in this article is very much a personalized account. Perhaps you have some experiences to share or suggestions to make. Perhaps you think that such a corpus should be done on a blog rather than on a Word document. Or maybe you use an Apple Mac and would like tell us how you would do it. Please feel free to do so in the comments.

And finally, to sum up, in this series we have looked at ways in which databases of language and the facilities for searching them can be used to do the following:

-

Create tailor-made language study activities for your learners which involve real and enaging examples of English.

-

Enhance your learners' linguistic understanding.

-

Show your learners how they can take responsibility for their own learning.

I hope that you have enjoyed the series.

The corpus principle: Introduction to corpora

In this six-part series, Jamie Keddie asks, 'What is a corpus?' and invites us to think about how we might use corpora in the classroom.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

The corpus principle – DIY Corpora

No comments yet