Can CLIL improve language and subject teaching at the same time? Phil Ball examines this bold claim by contrasting task design in native speaker and CLIL lessons, looking at the procedures and processes students undergo to acquire content knowledge.

A lot of claims are being made regarding the benefits of CLIL, so how does it work its alleged magic? How can it improve language and subject teaching at the same time? It sounds like a bold claim, but it may have some basis. Perhaps it is because by focusing more on procedural skills to get across the conceptual content, the teacher becomes more aware of the processes that the students need to pass through in order to assimilate the content. In this article, we look briefly at what we mean by 'language' in the academic context, and then consider a simple contrast between a lesson designed for native speakers and one designed for a CLIL context.

Language teaching flaws

We said in article two that language teaching seems to have problems related to its content. The basic flaw seems to reside in the fact that its conceptual content – topics, themes, stories – all of which can occur in a wide range of media, are subordinated to the underlying linguistic objective. The content that gives life to language, that illustrates it, that advertises it, that nurtures it – is all too often sacrificed on the altar of language practice. And of course, how can it be any different? If our objective is to assess language items and structures, then it is those aspects that we must teach.

Subject teaching flaws

But what about the other world of subject teaching? If we say, for now, that a major flaw in language teaching is one of content, we might be further tempted to suggest that language teachers, on the whole, are accustomed to dealing with content from a linguistic perspective, and not so much from a conceptual persepective. This is surely true. Language teachers are trained to use thematic content in a certain way (so that it becomes a vehicle for the illustration of language use), and we are arguing that the conceptual aspects (non-'linguistic') of that content are too often 'disposable'. Remember? Who cares about the Amazon rainforests as long as I can use the 2nd Conditional? Because that's what the teacher's going to test me on!

Subjects and their language

Subject teachers, on the other hand, are trained to do exactly the opposite. For them, no part of their syllabus content is either throwaway or disposable. A teacher of Biology will teach the concept of photosynthesis using all the content and procedure that is required to make that concept understood. What this teacher might not have considered are the language elements.

How can we talk of 'subject related skills' unless we also mention language? Surely, language is in itself 'content', and should be an explicit part of all subject-teaching?

Scientific discourse is different from the discourse of social science. Talking about art is very different from talking about mathematics. The differences exist on both a lexical and a structural basis, and even in primary school children are expected, to some extent, to understand, master and manipulate this language. This language is often referred to as text-type, and it is the crucial building-block in the conceptual architecture of any academic discipline.

Consider the following two examples. See if you can fill in the gaps.

- Fill 2 large beakers with hot tap water.

Fill the beakers to half full.

Place them on a flat surface a few cm apart.

Handle the thermometers carefully.

Read the temperatures then __________ them on a chart like this. - In the UK some twenty per cent of the population is of pensionable age. It is a proportion that is increasing. The map, (Figure C) shows that the life expectancy at birth is over 70 years in the developed world, __________ in the developing world it is much lower.

Lexis and grammar

You will have noticed, if you filled in the gaps successfully, that the examples use words that occur in many topical contexts. But the grammar of those examples shows how these words are used in the specific discourse style of the subjects, in these cases Science and Geography. In example 1, the gap could be filled by various verbs (write, put…) but the word 'record' is a more accurate reflection of the academic function required, in the context of a (basic) scientific experiment. To 'record' is not the same as to 'write'. In example 2, 'but' might be acceptable as the missing word, but the less common word 'whereas' is the better, more text-appropriate answer.

Students do not simply 'pick up' this type of language, to then use it immediately and correctly. By reading and working with the examples, they are being inducted into the world of subject-specific discourse, but the question of whether they learn to understand and then to use this type of language depends on many factors. Subject teachers need to be trained in order to make this language salient, to make it stand out and to help it do its conceptual work.

BICS & CALP

They sound like diseases, but don't worry; they're not. In 1979 a Canadian linguist called Jim Cummins introduced two very important acronyms ot the world of education – BICS and CALP. By BICS he meant Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills, which children pick up in the playground and at home and which is more related to what we might call 'conversational' survival. By CALP he meant Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency, which is the kind of language that you NEVER hear in the playground, and quite rightly so! The word 'whereas', in example 2 above, is at the weak end of the CALP scale because you could get away with the word 'but'. However, when you get to a scary word like 'photosynthesis' it's a whole different ball game.

Language as the key element in learning

By fusing the worlds of language and subject teaching, CLIL is helping everyone to focus on the importance of language as the key not just to academic success but as the key to normal educational practice. CLIL has not discovered this, of course. The Language Across the Curriculum movement in the 1980s in both the UK and the USA recognised the importance of language in the subject world, but again, in a CLIL context that works, this approach occurs almost by default. When you are not teaching native speakers, you tend to focus more on how you are going to get the concepts across, which brings us back to procedures.

'Skill' rhymes with 'CLIL'

We are constantly being told that the future of education resides in a new emphasis on skills and competences. The European Commission has published a list of 'key competences' for what it calls 'lifelong learning', and curriculum planners are now expected to incorporate these ideas across subject areas. This is good news for CLIL, because it is already functioning along these lines. There is no separation, in CLIL, of the worlds of concepts, procedures and language.

Consider the diffference between these two lessons – (1) from a standard social science native-speaker syllabus, and the other (2) from a CLIL-based programme using the same content.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Which activity is cognitively more challenging?

- Which activity is the most appropriate for building knowledge?

- Which activity offers the most opportunities for language use?

- When and for what would you use each activity?

(1) We have looked at some terms and concepts related to finances and to the accumulation of capital. Before we continue, try to match these definitions to their terms.

| Definition |

|---|

| People who supply us with materials |

| Part-owner of a company |

| Amount of money charged for the use of a loan |

| To set aside an amount of money recovered from investments in a given year |

| Portion of profits distributed to shareholders in proportion to their shareholdings |

| Portion of profits retained to finance expansion |

| Pay to employees in exchange for their labour |

| Money received by the company for the sale of goods or services |

| Portion of money received that remains after paying for materials, wages, investments |

| Term |

|---|

| Interest |

| Write off |

| Company capital |

| Suppliers |

| Earnings |

| Profits |

| Shareholder |

| Dividends |

| Wages |

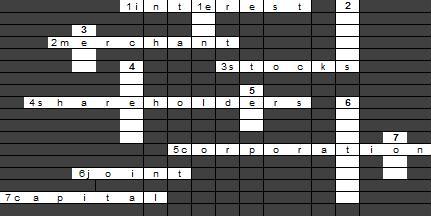

(2) Define these terms in pairs, as in the example given. Then find a partner from Group 'B' who has the other part of the crossword. Take it in turns to read out the definitions. The listener must try to supply the correct term.

(Group A)

|

Across: 1. When you borrow money, you normally have to pay this every month to the bank.

| Down: |

Procedures and cognition

In answer to a) – (which activity is more cognitively challenging?), we might answer, who cares? Both activities end up at the same conceptual point. But the crucial difference between the L1 activity and the CLIL equivalent is that the latter does not present the concepts all tied up in a perfect package. In Example 2, the students must go back over their materials and find out for themselves (in case they've forgotten) what the terms mean, and then they are obliged to frame them within a linguistic model that is provided, but only partially so. The example sentence (defining 'Interest') cannot be simply copied for the other terms. The concept will determine the exact language frames required. It's not easy, but it's possible. Nevertheless, it is procedurally rich.

In example 1, on the other hand, the language is provided, and although it is complex and requires a certain level of language to understand it, it still 'spoonfeeds' the students. All they have to do is to match. It is procedurally quite poor.

In answer to question 2 (Which activity builds knowledge the best?) the answer is obvious. Both activities have the same surface objective (to learn and understand the terms), but the differing processes suggest that the Crossword will be a more significant learning experience - even if it might lead to more mistakes and language errors along the way. A student is more likely to remember the lesson, and to remember the effort he or she made in fulfilling the procedural demands. Psycholinguists have been telling us for years that significant learning is more deeply processed and assimilated. So why not do it?

In answer to question 3 (Which activity offers the most opportunities for language use?) it hardly needs explanation. The activity is an information-gap type activity imported from the world of language teaching – it's not the kind of lesson you'd expect to see in a social science book – but consider the range of skills it works on. Writing (defining), reading (when you look at the gaps during the game phase), speaking and listening. Moreover, the listening required is intensive. The listener needs to understand, and therefore the speaker needs to be clear and grammatical! The students also need to work together cooperatively both in the preparation phase and in the game phase. In the matching activity, the teacher could feasibly say 'Do this for homework', which is kind of sad... Competences? Game over!

In answer to question 4, (When and for what would you use each activity?), you could argue that Activity 1 is better for just revising the concepts and moving on, and you'd probably be right. But the objective smacks of teacher convenience, as opposed to student benefit. With Activity 2, the teacher is bringing a whole lorry-load of educational objectives to the lesson, and pouring them onto the classroom floor. Who cares if it takes two lessons, and the other activity takes ten minutes? We're talking about educational pay-off here, and when CLIL is done well, that's what you get.

In the final article of the mini-series, we'll look at the range of activity types that CLIL seems best suited to.

Phil Ball

Topics

CLIL articles

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12Currently reading

Article: Language, concepts and procedures: Why CLIL does them better!

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

No comments yet